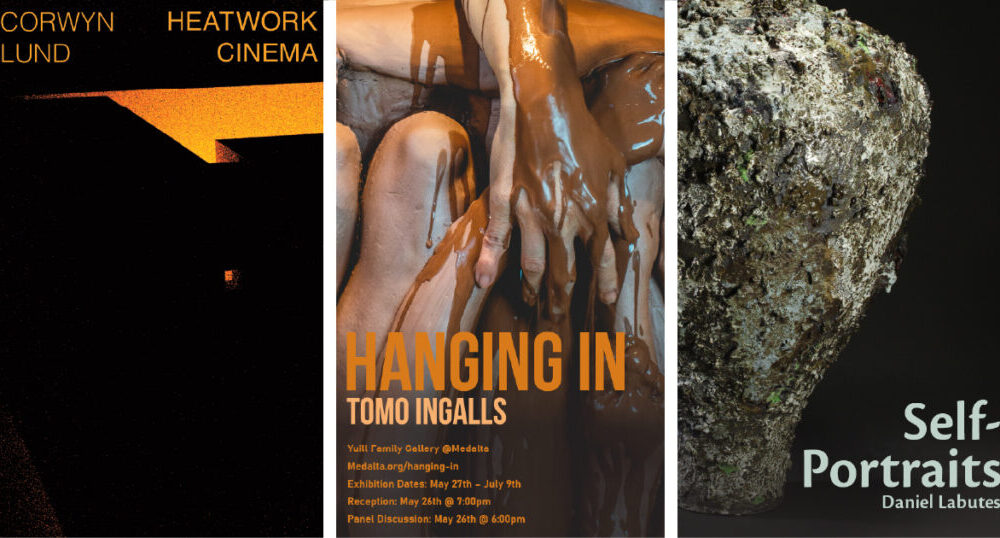

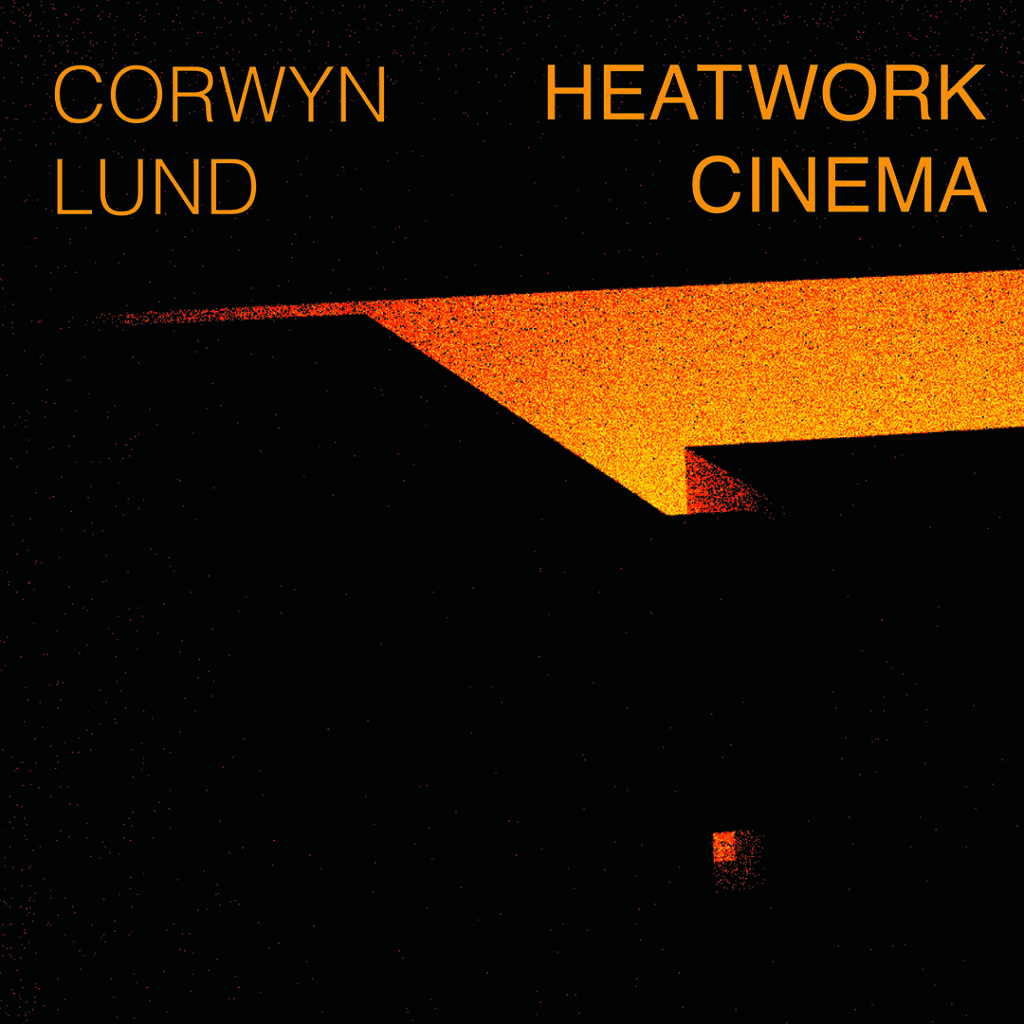

Heatwork Cinema

May 10, 2023

Black and White Gala 2023

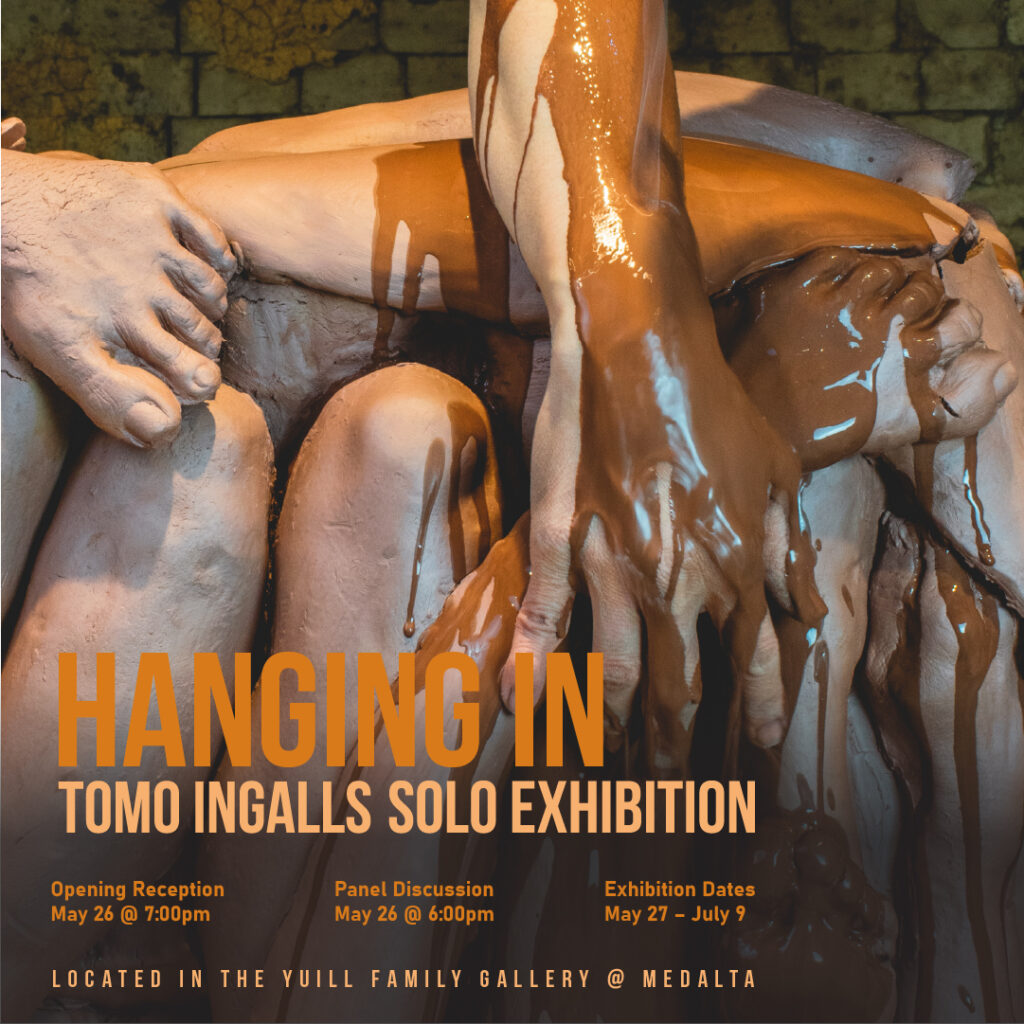

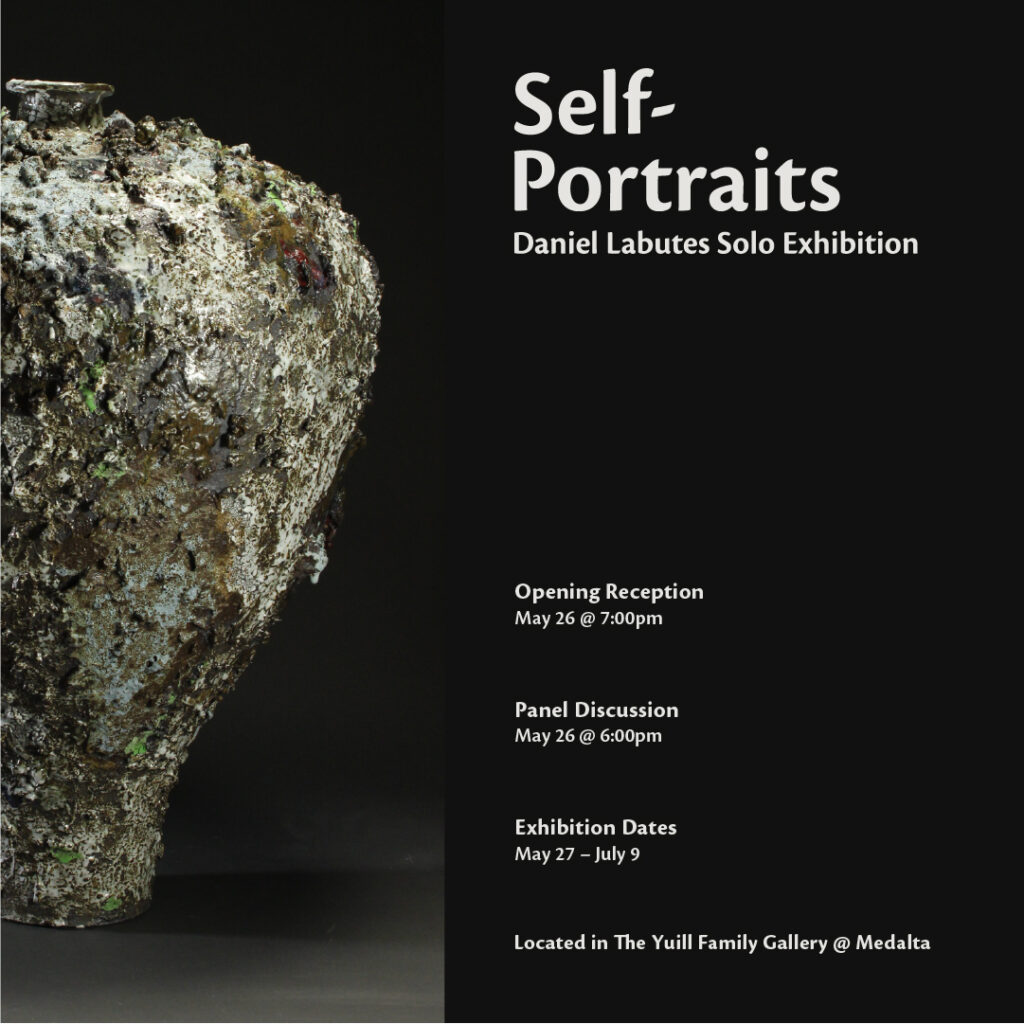

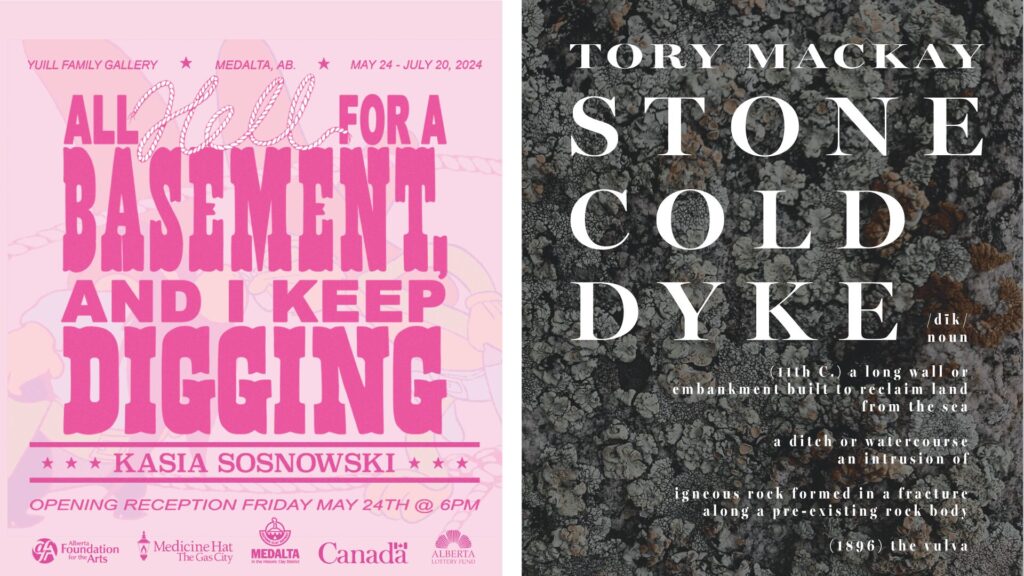

May 29, 2023Medalta International Artists in Residence presents three Solo Art Exhibitions by the 2022-2023 Residency year long term artists: Tomo Ingalls, Daniel Labutes, and Corwyn Lund.

Artists Panel Discussion and Opening Reception: Friday, May 26 at 6:00 – 9:00 pm

Curatorial Statement

“It seemed odd to me that all art disciplines had control over their materials—except for the art of ceramics. For example, the painters could pull out all the paints from their toolbox and mix the exact shade they envisioned. The printmakers, graphic designers, jewelers, photographers, sculptors, woodworkers—all had a vision of what they wanted and could control the materials of their mediums to achieve that result. The potters, on the other hand, had to glaze their work and put it into the ‘magic fire box’ as I liked to call it, and then wait to see what came out. After the kiln cooled, we all stood around and ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’ as the pieces were unloaded… The problem was that the pieces rarely looked like what the potters intended, and we spent the rest of the time assuring each other they were beautiful none-the-less. We learned to be open to the unexpected actions of the kiln and not have rigid expectations about the outcome.”

– John Britt, The Complete Guide to High-Fire Glazes: Glazing & Firing at Cone 10

When Amy Duval invited me to curate the year-end resident artist exhibition at The Shaw International Centre for Contemporary Ceramics at Medalta in Medicine Hat, Alberta, the artists included in the show had already been selected. Tomo Ingalls, Daniel Labutes, and Corwyn Lund had been working in their studios for the past year, and the gallery space was to be divided into three so they could each show the results of their efforts. The shows were to be considered separate, and I initially wondered what a curatorial role could contribute to what was already in place. From February to May of 2023, I met at intervals with the three artists and had the privilege of engaging in conversations that deepened as our time together unfolded. The work of each artist is totally distinct, unique, and innovative. At the same time, it became clear that the artists were working with similar concerns and interests. They were each developing compelling answers to shared questions. I decided to use my invitation as an opportunity to identify the connective tissue between each artist, reflected so well in the quote from John Britt. I didn’t want to impose my own research interests on the artists, but instead support them in their individual explorations, and see what rapport might emerge naturally. I decided to let my own curiosity about the tension that exists between art and craft, or Fine Art and Applied arts, play out in this curatorial text, and use the existing exhibition format as an opportunity to explore writer Yve Sedgewick’s idea that the way to resist binaries is to think about how things exist next to each other. There is a point at which things are not beside each other, but that is at the discretion of the person doing the arranging.

When Ingalls’, Labutes’, and Lund’s work is placed next to each other, several key themes emerge.

The imperfection of the body and the fact that it decays and is vulnerable, contrasted with the violence of structures and images that aim to deny or obscure this fact.

Each artist probes this area with a deliberate approach to how they make marks in their work, deciding whether the finished piece will show traces of their own body and process of making. Ingalls’ use of the body and its vulnerability in her work is explicit and literal. The artist’s hand is cast in plaster and used as a mold for clay. Wearing a blindfold, Ingalls is physically present and active during her performance, creating work with her hands in real-time, with no eyesight to guide them. Labutes creates and collapses vessels whose shape evokes traditional forms associated with production pottery, fragmenting their surface—delighting in the muck and mud that is irreducible from working with clay. In contrast, Lund’s departure point in the studio is the sceptic and clinical surface created by ceramic tile and how heat acts on bodies—pyroplasticity. His interest in using grids and the visual technology of perspective leads him to conflate kilns with cameras. Placed near Ingalls’ piles of limbs, Lund’s kiln echoes the horror of Holocaust extermination chambers. Labutes’ pots are pushed and dropped, displayed in a state of collapse, evoking a dorsal state of despair.

The role of chance and an audience’s hunger to be invited into a process that is fundamentally private.

Working with clay begins in the privacy of an artist’s studio, an individual process. The goal is for an end result that is shared, creating a ground for social interaction, whether that be through tableware, or a sculptural installation. Each artist’s approach to how much control they exert over the mark-making process in their work elaborates on the previous theme of physical vulnerability and places the social function of objects made with clay into the spotlight.

By obscuring her vision in the performance, Ingalls limits contact with the audience, increasing the intensity of her other senses. Her mark-making is driven by chance, determined moment to moment by her interaction with the clay. The audience’s access to the artist is prevented by four walls, and the difficulty of viewing Ingalls at work draws attention to their desire to do so. Labutes’ objects fold his process of making into the final piece. He collaborates with gravity, allowing it to have the ultimate say. The result could be described as a return to the joy and obsession of a beginner potter who bisques every piece they throw without discrimination, showing the full process of acquiring technical rigor and then unlearning it, present in one object. Lund re-creates the hunger of a potter, peering through the peephole in a kiln, waiting for their objects to fire and surrendering the result to the flame. The heat and light of the kiln makes it impossible to know how the pots will look once fired. By placing peepholes at varying heights, Lund re-creates this experience for visitors and draws attention to the physical effort involved in the creation process.

The shifting perception of objects and how their flickering image alters our experience.

Each artist combines a second artistic medium with clay to explore how minute changes can have significant impact on our experience or reading of an object. Labutes asks, “At which point does a drawing become a pot, a pot a drawing, an animation?” I am reminded of Saskatchewan potter John Elder saying, “Throwing on the wheel is just drawing in 3D.” Ingalls’ work asks, “At which point does a body become a person?” Lund’s work approaches the same concern from the opposite direction, asking, “At which point does the action of heat on bodies become an allegory for structural violence and environmental collapse?”.

Shame and harm, digested.

What strikes me most about each artist’s work is their courageous use of emotions like shame and fear of harm as source material for production. Each is imbued with threads of humour that make working with such difficult material possible. According to recent research into trauma and neuroscience, a person cannot commit difficult emotions to speech, paper, or physical form without having first processed them. The emotions must be re-visited in a safe, controlled, and supportive environment. An arrival at self-expression, joy, and connection to others, physiologically speaking, would not be possible without this review. The impulse to share what is most difficult and painful is a forceful declaration of survival and social optimism. The attempt to find words or shapes that convey the weight of despair or injustice builds bridges for the writer or maker to a safe harbour, leaving as its legacy a bridge for others to follow suit.

Like in the novel Mount Analogue by René Daumal, these clues and path markers may not be detected by others. The trail left by the artists may be seen by an audience as merely breadcrumbs or stones, not realizing the objects double as signposts. Differences in temperament, interest and training might prevent a viewer from registering any significance. How much responsibility for the legibility of an object lies with the maker, with the audience? To share or draw attention to challenging experiences is a declaration of trust in the resilience of an intended audience and stakes a claim in creating a space where empathy and compassion can be practiced as a public.

Rebecca La Marre, 2023

About Rebecca La Marre

Rebecca La Marre is a queer artist with a writing, research and performance practice. She uses clay and text to give form to questions about what it means to be a person in the world, and how ideological structures, religious trauma, language, and ritual can shape bodies. Her performances and texts are driven by what she reads and make use of materials that include clay, text, and the human voice. The first person to teach her about clay was her grandmother, an artist who exhibited her work in domestic settings and craft markets.

Her work is exhibited and published internationally. Venues include the Serpentine Gallery, MOMA PS1, and the Darling Foundry. Her writing has been published in journals and periodicals including the Happy Hypocrite, Organism for Poetic Research, Poetry is Dead, and Through Europe. She is the former editor and publications coordinator for Remai Modern, an emeritus

commissioning editor for E.R.O.S. Journal in London, UK, and founder of Apophony Press in Saskatoon, SK.

She holds a Masters in Art Writing from Goldsmiths, University of London, and is the recipient of funding from SK Arts, The British Arts Council, The Québec Council for the Arts, and the Federal Government of Canada.